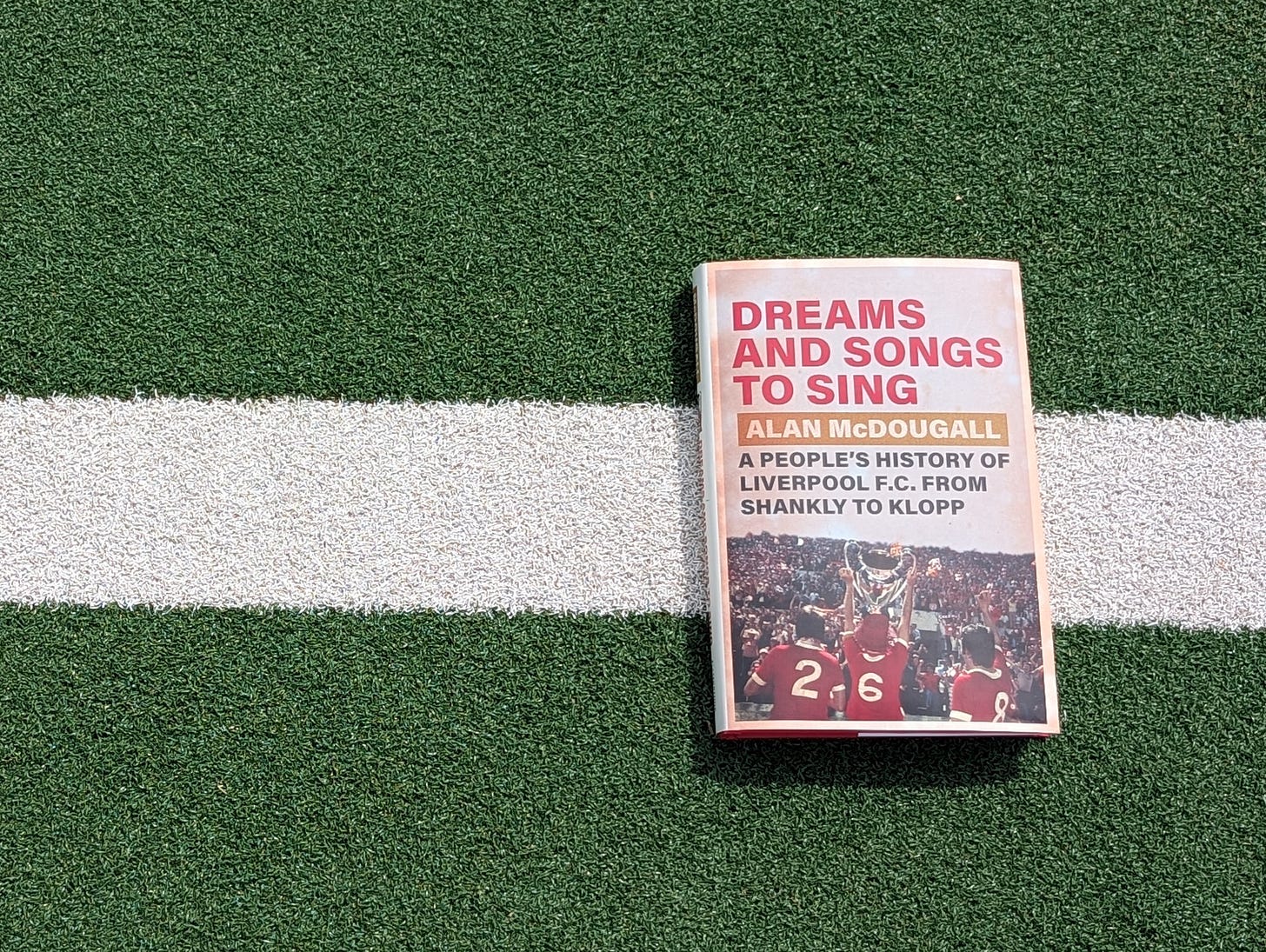

The following is an extract from the book Dreams and Songs to Sing: A People’s History of Liverpool FC From Shankly to Klopp by Alan McDougall and published by Cambridge University Press. It is available for purchase in Australia, Canada, Germany, Liverpool, New Zealand, Norway, the UK, the United States, & around the world.

It’s a routine tackle in 1981. Call it, if you’re being kind, a forward’s challenge. Bayern Munich winger Karl Del’Haye has just hacked down Kenny Dalglish, Liverpool’s best attacker. We’re five minutes into the second leg of the European Cup semi-final in Bayern’s Olympic Stadium. It’s 0–0 on aggregate. Dalglish hobbles around for a few minutes on a sore ankle but can’t continue. Liverpool are already short-handed. Half the back four, Colin Irwin and Richard Money, are reserves. Could they throw another inexperienced player into the mix?

As Dalglish tries to run off his injury, Liverpool’s subs warm up. Jimmy Case is the old hand. The others are young. Israeli defender Avi Cohen, striker Ian Rush, and twenty-two-year-old Howard Gayle, a winger from Toxteth, who made his debut the previous October. Liverpool had existed for eighty-five years when Gayle signed a professional contract in 1977. He was the club’s first Black player. As he stretches by the running track on a warm night, Gayle hears familiar sounds from the stands. Monkey noises. He sees ‘a few grown men making Nazi salutes’.1 Ronnie Moran calls the subs back to the bench. Bob Paisley has decided. Gayle will replace Dalglish.

Howard Gayle’s Liverpool career was short – five games and one goal, from October 1980 to May 1981 – but it can be condensed into the sixty-one minutes he played in Munich on 22 April 1981. On the left, Gayle is almost unplayable. He’s cleaned out by Wolfgang Dremmler on the half-hour mark, a blatant penalty that referee António Garrido doesn’t give. He’s hacked down again after a surging run early in the second half. Every time Gayle’s on the ball, the monkey chants can be heard. He gets a yellow card for what the Echo called ‘a wild tackle’ on Dremmler (‘really a silly lad’, is Barry Davies’ school- masterly commentary). It looks, to my eyes, innocuous. Paisley decides to sub the sub, and, after seventy minutes, Jimmy Case replaces Gayle. With seven minutes left, Ray Kennedy gets the decisive away goal. Karl- Heinz Rummenigge’s equaliser four minutes later is meaningless. Liverpool are through to a third European Cup final in five years. It doesn’t happen without Howard Gayle. ‘He ran Bayern ragged with his pace’, Paisley reflected. ‘Howard’s performance was outstanding’, said teammate David Johnson. ‘It was gritty, it was hard and it was courageous’.2

***

There was a shadow on Gayle’s great night. He wasn’t trusted to see the game out. Paisley substituted Gayle partly because he was tiring but mostly because he feared Gayle would ‘retaliate’ against Bayern’s provocations and get a red card. The consensus around Anfield, where Gayle graduated from a brilliant reserve team, was that ‘Howard had a chip on his shoulder’. He was bitter, impatient, ‘a bit, you know, black power’. Gayle was once sent off for punching a player who called him a ‘n*****’. More Malcolm X than Martin Luther King, he didn’t turn the other cheek. Subconsciously at least, all this played into the decision to substitute Gayle. The odds were stacked against him, as they were against most Black players in the 70s, who, to list a few stereotypes, didn’t like cold weather, got easily discouraged, and could be hot- headed. Gayle never got the chance to build on Munich, or on his first Liverpool goal, at home to Spurs a few days later.

Temperament, that chip on the shoulder, was often cited as a reason for Gayle’s failure to make the grade. So was quality. ‘He really wasn’t up to the standard that we required’, said Peter Robinson. This of a player who outscored Ian Rush in the reserves, was highly regarded by Graeme Souness, and of whom Brian Glanville wrote after the Spurs game: ‘I do strongly believe that this fast, brave, skilled player with the telescopic legs can do a great deal for the club’. Bruce Grobbelaar’s temperament was forged in the jungles of white supremacist Rhodesia, where he fought for Ian Smith’s minority rule government against the Black revolutionaries of ZANU and ZAPU.

Mistakes littered Grobbelaar’s early Liverpool career, which began, like Gayle’s, in 1981. Grobbelaar got time to develop. Gayle, whose early appearances were so promising, didn’t.

Bill Shankly’s welcome for new Liverpool players, 1968: ‘Here we have no interest in politics or religion. It doesn’t matter what you are so long as you can play football’. It’s a nice idea. That where you come from doesn’t matter, that football’s blind to anything but ability and application. But it’s not true. Liverpool in the late 70s had one of the oldest, most integrated Black communities in Britain. But the Black population, in historian Ray Costello’s words, was ‘an invisible people’. And the city’s top football club wasn’t a bastion of racial tolerance. Ronnie Hughes remembers sitting in the Paddock in the late 60s, hearing abuse of West Ham’s Black striker, Clyde Best. Ian Callaghan, ever the gentleman, came over and told the offending fans to shut up. The Liverpool crowd wasn’t immune to making the monkey noises Howard Gayle heard in Munich. Calling an opposition player a ‘black bastard’. Chanting ‘Coco Pops’, ‘Day-O’, or worse. All part of the terrain, part of the times. Like hiring a comedian for the players’ Christmas party, who approached Liverpool’s only Black player, poured a bowl of flour over his head, and said, ‘now try walking into fucking Toxteth’. Gayle and his peers were meant to shrug it off. Thick skin. Strong shoulders. Get rid of that chip.

***

Though he grew up in the mostly white suburb of Norris Green, Howard Gayle was born in 1958 in Toxteth. Better put, he was born in Liverpool 8. Just south of the city centre, the district commonly called Toxteth was, in Gayle’s day, two neighbourhoods. The nicer bits, close to Sefton Park and Princes Park. And the more ethnically diverse area south of Upper Parliament Street, home to much of Liverpool’s Black population. Known to locals not as Toxteth, but as Liverpool 8 or Granby, after its main thoroughfare, Granby Street.

Chris and Eddie Amoo, founder members of Liverpool’s greatest Black pop band, the Real Thing, grew up on the (slightly) posher northern side of the Toxteth tracks, on Tennyson Street, long since bulldozed, and then at their grandmother’s flat in Myrtle Gardens, where they were the only Black family. Like many 80s kids, I knew the Real Thing from their 1976 UK number one, ‘You to Me Are Everything’, an irresistibly catchy song, re-released in 1986, to which my sister could never remember the words. But the band’s second album featured work a far cry from ‘You to Me’ or the equally infectious ‘Can’t Get By Without You’. Channeling 70s Stevie Wonder, 4 From 8 finished with a song cycle, ‘Liverpool 8’, about the area where the band grew up, from Stanhope Street down to the docks. The centre point was ‘Children of the Ghetto’:

Children of the ghetto

Running wild and free

In the concrete jungle

Filled with misery

There’s no inspiration

To brighten up their day

So out of desperation

I would like to say

Children of the ghetto

Keep your head

To the sky.

The song, recalled journalist Ed Vulliamy, was the soundtrack to Liverpool’s summer of 1981, ‘blaring out the windows of Liverpool 8’, including his bedroom window on Catharine Street.

Less than three months after Howard Gayle’s finest hour, Liverpool 8 went up in flames. At 9.30 p.m. on Friday 3 July 1981, an unmarked police car stopped a young Black man on a motorbike at the corner of Granby Street and Selbourne Street. As in the LA district of Watts in 1965, a ‘routine’ police check – the ‘stop and search’ that disproportionately targeted young Black men – sparked an uprising. A crowd gathered to protest. One man, Leroy Alphonse Cooper, was arrested. Stones struck police vehicles. Howard Gayle called what happened next ‘simply an event where black communities stood up against the police after years of mistreatment’. Granby ward councillor Margaret Simey told Radio Merseyside things were so bad people ‘ought to riot’.

Over the weekend, protest became insurrection. Buildings were set ablaze, including the Rialto, once a dancehall that refused admission to ‘coloureds’ and later a factory that refused to employ them. Shops were looted. On 6 July, for the first time outside Northern Ireland, police used CS gas on protestors. There were further confrontations at the end of the month, when the police response – this time, also imported from Northern Ireland, driving Land Rovers into crowds to disperse them – killed a disabled man, David Moore. Police and protestors clashed at Moore’s funeral on 11 August. An anti-police march four days later demanded the resignation of the Chief Constable of Merseyside, Kenneth Oxford, who’d blamed unrest on ‘a crowd of black hooligans intent on making life unbearable and indulging in criminal activities’ Oxford was knighted in 1988.

One fatality, 150 buildings burnt to the ground, £11 million of damage, 462 arrests, and 781 police officers injured. The Toxteth riots, as they quickly came to be known, were part of a year of protest against racist policing, youth unemployment, and economic deprivation in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain. It began with the Brixton riots in April. Confrontations followed in July, in London again (Southall), Birmingham (Handsworth), Leeds (Chapeltown), Manchester (Moss Side), and other cities. ‘A riot is the language of the unheard’, said Martin Luther King in 1968. King was speaking after a spate of ‘riots’, or risings, across American cities in 1967, notably in Detroit, like Liverpool a one-industry city with a brilliant music scene and a large, disenfranchised Black population. Viewing Detroit from a helicopter after the violence there in July (forty- three deaths), Michigan governor George Romney said it ‘looks like a city that has been bombed’. One eyewitness in Toxteth fourteen years later called the scene on the night of 3 July ‘a Hieronymus Bosch painting of Hell’.

In Liverpool, like Detroit, unrest triggered enquiries. The Kerner Report (1968) warned that the United States was ‘moving towards two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal’, as if it had ever been anything else. The Scarman Report, a government enquiry into the Brixton riots, extended nationwide after the events of the summer, blamed ‘racial disadvantage’ and heavy-handed policing for unrest, but refuted the idea of institutional racism. Margaret Thatcher, meanwhile, dispatched her Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine, to Liverpool. As ‘Minister for Merseyside’, he promised market-driven solutions to the city’s problems. Heseltine’s largesse grabbed headlines, particularly the refashioning of the Albert Dock as a tourist venue. But money and jobs didn’t reach residents of L8, where not much changed for the better. In Liverpool, as in Detroit, the biggest takeaways from the riots were punitive. Tougher policing, the creation of no-go areas, and inner-city reputations of decline and criminality that took decades to shake off.

***

‘The End hopes to try to get Liverpool out of its rut’. That’s the opening line of the editorial in Issue 1 of a new magazine for ‘the youth of Liverpool’, published in October 1981. Issue 1 reviewed the Specials’ recent concert at the Royal Court in Liverpool. The band’s summer number one, ‘Ghost Town’ – a sparse, brooding anthem about unemployment, violence, and urban decay – could have hardly felt more relevant. Jerry Dammers wrote it after touring the UK and seeing the impact of Thatcher’s monetarist revolution: ‘in Liverpool all the shops were shuttered up, everything was closing down’.

The End was founded by two white Scousers from Cantril Farm, Phil Jones and Peter Hooton. The pair never claimed to speak for the city’s Black youth but were alive to the despair they saw around them, in Liverpool 8 and in the sink estate where they lived, a place that, like Netherley, where the poet Paul Farley grew up, ‘feels like the end of the line’. Among The End’s readers and writers, as in many reports on the Toxteth riots, Liverpool’s problems were tied to class as well as race. As one poem from July 1982 put it: ‘Black boy, white boy/All in the same boat/Dole drums, no joy/Didn’t bother to vote’.

John Peel, Radio 1 DJ and LFC fan, had no doubt: ‘My favourite magazine of all is The End from Liverpool which concerns itself with music, beer and football. The very stuff of life itself’. It’s a bit of a misleading description. The End was more about music than football. Hooton, like Peel, was a Liverpool fan. He wanted to create something funny and provocative, something you could sell at the match and at concerts. Previous music fanzines took themselves very seriously and didn’t talk about football at all, just as nobody talked about the game at Eric’s, Liverpool’s coolest music venue from 1976 to 1980. The End would at least broach that taboo subject. ‘I had a gut feeling’, Hooton told me in 2016, ‘it might work’.

Initially mistaken for a student mag, The End soon did lively business in pubs around Anfield and Goodison, outside Dead Kennedys gigs, and at Probe Records and HMV. Its reputation spread beyond Liverpool. Paul Du Noyer and Stuart Maconie championed The End at New Musical Express, the UK’s most important music paper. The editors made their television bow in 1983, on the BBC’s Oxford Road Show, a music programme from Manchester. John Peel, in a Liverpool tracksuit top, asked them about ‘professional Liverpudlians’ (an ironic question, perhaps, for a privately educated bloke from Heswall), the magazine’s origins, and its attitude to hooligans. By this point The End was, in Hooton’s words, ‘a phenomenon’, a cult magazine with a national following. People wanted to be in it. Among the luminaries interviewed between 1981 and 1988 were Peel, the Clash, Billy Bragg, Alan Bleasdale, Alexei Sayle, and Derek Hatton.

Anarchic humour, anger, music, politics, fashion, and football. The End messily captured the spirit of 1981 in Liverpool. Perhaps that’s why football, and LFC in particular – the city’s biggest success story – took a back seat to more urgent topics. The game comes up quite rarely, especially in the early years, unless it’s to take the piss out of hooligans. There’s discussion of Liverpool’s ‘minge-bag’ owners selling Kop tickets to Man United fans in 1982. A close-to-the-bone Munich spoof on the ‘Warsaw air disaster’, following a rocky flight to Poland for Liverpool’s game against Widzew Łódźin 1983. Later, there’s staunch defence of Liverpool fans at Heysel. And condemnation of Scousers who threw bananas at John Barnes: ‘if both sets of fans can’t applaud probably the most skillful player in Britain .. . then there’s nothing down for any of us’. The End is a barometer of Liverpool in the 80s, a decade of laughter in the dark.

***

In the summer of 1979, Liverpool completed an unlikely transfer, paying Maccabi Tel Aviv £200,000 for Israeli centre back Avi Cohen. Cohen’s wife Dorit felt the scale of the culture shock in their new home. ‘The beginning was hard .. . and the local accent was hard. [Liverpool] was grey and depressing, the winter harsh’. Torbjørn Flatin, a Liverpool fan from Norway, had similar impressions when he arrived in the city in 1980. ‘It was very bleak, a lot of unemployment, a lot of wasteland ... very grey’.

The Toxteth riots prompted lurid headlines about Liverpool’s inner-city crisis. A concerned Bob Paisley encouraged Howard Gayle to leave L8. He reluctantly complied, buying a place a few miles away in Mossley Hill. For the law-and-order camp, Gayle’s birthplace was a war zone, ‘the sort of area’, sniffed the Sunday Telegraph, ‘where it is hard to tell the riot damage from the urban decay’. Even the more sympathetic Daily Mirror described Liverpool 8 as ‘virtually a black ghetto’, a place of ‘savage rioting’, squalor, and desolation. In 1981, between 70 and 80 per cent of people were out of work there. The figure was higher for the group facing the most hostile labour market, young Black men. Derek Murray worked in the early 80s at the Merseyside Caribbean Centre on Upper Parliament Street. The situation for Black kids, he recalled, ‘was absolutely shameful’.

Unemployment was coming to dominate life on Merseyside. It was a long-term trend, dating back to Liverpool’s post-war decline as a seaport and its lack of other focal points in a deindustrialising world of global capital and consumer goods. Containerisation required far fewer dock workers and rendered many of Liverpool’s docks obsolete as commercial centres. The UK’s entry into the Common Market in 1973 benefitted eastern ports like Felixstowe and Grimsby, closer to Europe than Atlantic-facing Liverpool. Liverpool’s share of ship arrivals in the UK halved from 1966 to 1994. Unemployment in the port districts was nearly 30 per cent in the late 70s. In 1977, half of the city’s unemployed were aged between sixteen and twenty-four. It could take two or three years to find your first job, if you could find one at all.

With the city’s most reliable source of employment no longer reliable, people, especially young people, left in droves. Liverpool’s population declined faster than that of any other British city, from 856,000 in 1931 to 510,000 in 1981. Inner-city areas like Toxteth were rapidly depopulated. Some people were relocated to new council estates in outlying areas like Kirkby, Cantril Farm, Netherley, or, like Howard Gayle’s family, Norris Green. Many went further afield, creating a huge Scouse diaspora. Letters and poems to The End suggest the pain this exodus caused. Here’s ‘Brighton Blues’ from Michelle in 1983: ‘Sitting here swigging a cheap bottle of wine/Kidding everyone at home I’m having a good time’. Along the south coast in Bournemouth, the 5,000 Scousers became a local byword for crime.

For most of its inhabitants, Liverpool had always been a place of precarity, of casual labour on the docks and the kind of urban squalor documented in James Samuelson’s The Children of Our Slums, published in 1911, when the seaport was at its commercial peak and Walter Aubrey Thomas’ Royal Liver Building opened for business. The city’s decline in the 80s was as much reputational as economic. A national narrative about Liverpool and its bolshie, whiny population hardened. Scallies stealing your hub caps while you parked outside the ground. Yosser Hughes intoning ‘Gizza job’ in Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Blackstuff. And a football chant everyone was singing by the mid-80s: ‘In your Liverpool slums’.

Liverpool’s economic decline began long before 1979 but Margaret Thatcher’s government accelerated the process. Patrick Minford, professor of applied economics at Liverpool University, was one of the British monetarists captivated by the free-market ideas of American economist Milton Friedman. Friedman’s obsession was curbing inflation through controlling the amount of money in circulation and cutting public spending. In the early 80s, Minford found ‘a case study on [his] doorstep’. His ‘Liverpool model’, according to ‘The problem of unemployment’ (1981), predicted a 15 per cent cut in social security benefits plus a return to wage levels of the mid-60s would cut UK unemployment by 1.5 million.

What remains when everything falls apart? The answer, in Liverpool in the 80s, was football.

‘Unemployment’, Minford wrote in his 1981 essay, ‘is ... unlikely to cause major social unrest’. A few weeks later, the Toxteth riots, around the corner from his office on the Liverpool University campus, dynamited this argument. Racist policing was the spark, but unemployment – officially 39.6 per cent in the Granby ward in 1981, but much higher for certain groups in certain neighbourhoods – contributed to the conflagration. The ‘Liverpool model’, it transpired, underestimated how big a spoonful of unemployment medicine was needed to get the British economy ‘on track’. The national jobless figure was 2.24 million in 1980, 2.9 million in 1981, and over three million in 1983 – hardly a recipe for slashing benefits. Liverpool became the poster child for the devastation of mass unemployment, the opposite of what Minford’s computer programme had envisaged. While Michael Heseltine’s spending spree suggested a government commitment to regenerating Liverpool (if not Liverpool 8), less wet colleagues objected to throwing money at a troublesome city. Responding to Heseltine’s request for £100 million for Liverpool over the next two years, the Chancellor Geoffrey Howe asked in 1981: ‘Isn’t this pumping water uphill? Should we go rather for “managed decline”? This is not a term for use, even privately. It is much too negative, when it must imply a sustained effort to absorb Liverpool manpower elsewhere’.

One side of the battlelines was drawn. In 1983, the other side took firmer shape, when Derek Hatton, flashy alumnus of the Liverpool Institute and Everton supporter, became Deputy Leader of Liverpool City Council. Hatton represented Militant, the far-left Trotskyist wing of the Labour Party. He became the public face of Liverpool’s effective civil war with the Thatcher government, furthering the city’s perceived isolation from the rest of the country (in fact, Liverpool’s difficulties weren’t so different from those of Glasgow or Tyneside) and from much of Hatton’s party. As Labour under Neil Kinnock quietly dropped socialism, Militant pushed a radical socialist agenda in Liverpool. The Tory government, meanwhile, privately at least, left the city to its post- industrial devices. The resulting conflicts – between Whitehall and Liverpool City Council, and between Labour and Liverpool City Council – took a toll locally. Julian Buchanan, working as a probation officer, remembers ‘a hugely painful time’. Critical of Thatcherism and a man of the left, Buchanan wasn’t enamoured either with the grand- standing Hatton, ‘a businessman up his own arse’. He felt isolated and alienated, both from Thatcher’s monetarist revolution and the Militant faction running Liverpool into the ground. In 80s Liverpool, Buchanan concluded, ‘self-respect became replaced with aggression and violence basically, and hate and fights’. To Peter Furmedge, ‘Liverpool became a harder place’, a hardness embodied by Yosser Hughes in Boys from the Blackstuff. His default response to the despair of unemployment is the headbutt. ‘Is this all there is?’

What remains when everything falls apart? The answer, in Liverpool in the 80s, was football. Merseyside still produced successful musicians, many of them – from the Teardrop Explodes and Echo & the Bunnymen to Frankie Goes to Hollywood and OMD – crossbred and connected at Eric’s, the post-punk club on Mathew Street. Through soap operas (Brookside), writers like Alan Bleasdale (Blackstuff, Scully) and Carla Lane (Bread), and 60s holdouts like Cilla Black, the city’s presence on British television was stronger than ever. But football, more than anything else, polished Liverpool’s tarnished civic identity. Liverpool and Everton won eight of the ten championships contested between 1980 and 1990, plus three European trophies, four League Cups, and three FA Cups. The Mighty Wah’s Pete Wylie wondered in 1984 if ‘sometimes people attach too much importance to football’. But he was in the minority. When the Sunday Times asked Derek Hatton a similar question a year later, Hatton’s reply was ‘as snappy as his suit’: ‘That’s like asking if mice care too much about cheese. Football has always been at the heart of this city’.

***

Between Howard Gayle’s Munich cameo and Liverpool 8 going up in flames, Liverpool FC won a third European Cup in five seasons, defeating Real Madrid 1–0 in Paris, thanks to Alan Kennedy’s late goal. Gayle stayed on the bench at the Parc des Princes on 27 May. He’d already played his last game for the club. Paisley’s team had endured a rare poor league campaign, but in Europe, reported David Lacey, they were old hands. ‘Pacing their game carefully, reluctant to waste possession with ambitious passes .. . they always kept their movements wide and always the man with the ball had good support as colleagues ran intelligently into space’. Phil Thompson, Kirkby lad and club captain, lifted the trophy, and took it back to his local pub, The Falcon. Big Ears sat on a shelf behind the bar, alongside pub team trophies. ‘We all got a bit plastered’.

Half a million people welcomed LFC home on 28 May, a world away from the crowds that would gather in Liverpool 8 five weeks later. Jacqui and Stephen Small show off their ‘Barney’ mascot, presented to Alan ‘Barney Rubble’ Kennedy. Three-year-old Julie Cresby celebrates with an ice-cream, Kopite Alan Bowyer with a beer, in his Liverbird- crested stovepipe hat. This is the public face that Liverpool (well, the red half at least) liked to present to the world. The football team as civic ambassadors. ‘Goodness knows Merseyside needs something to shout about and the Reds have supplied that much-needed tonic’, said an Echo editorial. ‘Liverpool F.C. have demonstrated that in one sphere at least we can do something superbly well’.

On the day of the parade, two front page Echo headlines: ‘Welcome home, you super Reds!’ and ‘Gloom as more join Mersey dole queue’. As the city of Liverpool was buffeted by political and economic turmoil, LFC sailed serenely towards trophy-laden horizons, using the template, and many of the personnel, Bill Shankly had installed two decades earlier. Under Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan, it was business as usual between 1981 and 1984. Two European Cups, four League Cups, and three championships. A ridiculous record that impressed observers even as they got bored by it and struggled to find metaphors for Liverpool’s dominance. Steamroller. Juggernaut. Red machine.

‘The club has a touch of communism – in the strictly non- political sense’, wrote Bob Paisley in 1983. Craig Johnston, who joined Liverpool in 1981 from Middlesbrough, remembered his first training session in freezing conditions. He dressed in full training gear, including tracksuit bottoms. Everyone else had bare legs, including Paisley, who waddled onto the pitch at Melwood in ‘baggy shorts’, blue veins bulging on his white and ‘ancient’ pins. Johnston couldn’t believe one of the world’s best teams could be this spartan. He soon learned it was ‘the Liverpool way’. No tall poppies (Johnston’s Porsche, registration plate ‘Roo 1’, didn’t go down well). Train as you play (i.e., in shorts). Simplicity and continuity. When Paisley retired in 1983, after Liverpool won the league so easily their mostly drunk players took two points from the final seven matches, assistant manager Joe Fagan replaced him. Why change a winning formula?

***

Watching from the stands in 1983/84, journalist Brian Reade had an uncomfortable feeling. ‘I wasn’t getting the same kick out of it as I used to’. Too often, Liverpool games were ‘Lord Mayor’s processions’. ‘Disgustingly, I was bored with success’. The average crowd in 1978/79, when one of the great Liverpool teams conceded four goals at Anfield all season, was 46,510, a shade behind Manchester United as the league’s best. Two years later, the Anfield average fell to 37,646, almost 8,000 behind Old Trafford. It bottomed out at 32,022 in 1983/ 84, when Joe Fagan’s side won a treble of European Cup, league, and League Cup.

Apathy wasn’t the only reason for the drop-off. You could factor in inner-city depopulation, alternative leisure options, increased ticket prices, and violence – or the threat of it. A Daily Post survey from 1977 revealed 40 per cent of respondents had stopped going to matches because of hooliganism. Often these were aways, with Old Trafford viewed as especially dangerous. But one supporter recounted bricks being thrown at Anfield: ‘This has deterred me taking children in future’.

Heysel caused dismay and denial in Liverpool because LFC supporters weren’t seen as the worst hooligan offenders. Liverpool didn’t have large ‘crews’ who wrecked stadiums and fought at home and abroad. Troublemakers were more into drinking, fashion, thieving, fare-dodging, and bunking into games for free. Fighting too, yes, but only when unavoidable. As Nicky Allt’s account of life with the Anfield Road Crew suggests, there’s an element of having your cake and eating it about the ‘distinctiveness’ of scally fan culture. How big is the difference between ‘a nailed-on hooligan’ and, as Allt describes his younger self, ‘a little football hooligan’? A photo from 1980 shows a Spurs fan being led away from Anfield by policemen, holding his hand to his neck, a victim of the ‘Anny Road Darts Team’.

One factor bigger than hooliganism kept people away. Large numbers of people couldn’t afford to go any more. By far the biggest single-season drop in average attendance at Anfield occurred between 1979/80 (44,758), when the Thatcher government had just come to power, and 1980/81 (37,646), when its monetarist revolution began to bite, causing a recession and mass unemployment. In the early 80s, remembered Adrian Killen, people sold season tickets because they were out of work. Julian Buchanan recalled the stark realisation from this time: ‘people were gobsmacked to discover that you couldn’t have a job for life anymore’. The certainties of the post-war consensus, from steady employment to the welfare state, were crumbling. Buchanan wasn’t the only one who kept his head down and ‘move[d] away from football’.

There was, by the mid-80s, a growing disconnect between the club and local supporters. For William Twentyman, son of the club’s chief scout Geoff, the family club he grew up around became an increasingly commercial entity, ‘a closed shop’ that kept supporters distant. The End was scathing about the LFC top brass. Seats on the Kop, the editors predicted in 1982, were ‘only a matter of time because Liverpool think only in money terms’. A year later, the magazine published a poem by Fred Quimby, ‘a true Kopite who doesn’t like being shat on’: ‘Isn’t that a dolites luck/John Smith you couldn’t give a fuck .. . You keep throwing shit in the Kops face/You shitbag Smith get out of this place/ Go back to Lower Heswall you fucking Tory/Cos I don’t want your fucking glory’.

The End was intensely local. Its writers felt humorously protective about Liverpool and often distrusted people from elsewhere (they also, to be fair, didn’t think much of people from Liverpool either, e.g., Beatles nostalgists, politicians, and ‘professional Scousers’ like Jimmy Tarbuck). Pretty much anyone outside the city, bar John Peel, was a ‘wool’, an outsider. Runcorn was as bad as Reykjavik in this regard; in fact, it was worse, as wools generally lived nearby, ‘in the Pennine regions and some parts of Lancashire’. Will Sergeant, who grew up, like my cousins, in Melling, eight miles from the city centre, got called a ‘woolly back’. Prime areas for sightings were the Wirral, Wigan, Widnes, and Warrington. ‘Wool Central’ was Leeds, whose fans were mercilessly mocked.

‘Wools’ weren’t the same as ‘out-of-towners’, but scally culture had little time for either. Liverpool’s a proudly international city, but it also has a proudly piss-taking local identity, which sometimes defaults to viewing non-Liverpudlians as less authentic, less cool supporters (and people). Tensions between the club’s local support and its wider fan bases sharpened in the 80s. As local crowds fell away, supporters from elsewhere took up some of the slack. The End complained in 1983 about LFC ‘selling the club like a big business and wooing all sorts of wools. The Kop’s all Welsh now’. Around the same time, Adrian Killen noticed people from outside the city standing on the Kop. Success brought in fans from ‘here, there, and everywhere’.

Carsten Nippert’s first match was the European Cup semi-final vs. Bayern in the Olympic Stadium in April 1981. He and his Mum gave their spare ticket to a ticketless Scouser. In the same year, a group of Icelandic LFC supporters from Akureyri, including Gunnar Sveinarsson, Oskar Gudmundsson, and Sigurdur Jonsson, travelled to London for the League Cup final vs. West Ham and to Paris for the European Cup final vs. Real Madrid. Stuck behind the Iron Curtain in Chorzów, Poland, twenty-three-year-old Damien Garczorz listened to commentaries on the BBC World Service and collected LFC cuttings, photos, and programmes. After Liverpool lost to Widzew Łódźin the 1982/83 European Cup, ‘I was crying! For about three days I could not recover from depression’. Wojtek Kaminski, from Kędzierzyn-Koźle, a small town an hour west of Katowice, was more ambitious. He founded a supporters’ club at the University of Silesia, organised a welcome parade for the Liverpool team that played Lech Poznańin 1984 and, in the same year, made his first visit to Anfield.

***

After Bob Paisley’s retirement, the Boot Room succession was strictly observed, as it had been in 1974. On 1 July 1983, Paisley’s assistant Joe Fagan – a Litherland lad who played 168 times for the club before joining Phil Taylor’s staff in 1958 – took the managerial reins. The quietest of the coaches, and the man closest to the players (hence ‘Uncle Joe’), Fagan was the most low-key man in a low-key set-up. He lived around the corner from Anfield in a modest semi-detached house.

When Watford owner Elton John visited the Boot Room for the trad- itional post-match drink, he asked Fagan for a pink gin. ‘You can have a brown ale, a Guiness or a scotch and that’s your lot’, was the reply. Unpretentious, almost parodically modest. That was Joe Fagan. Like Paisley, he took the job because he was supposed to, not because he wanted it. ‘I was in a rut when they offered it to me. Ronnie Moran and Roy Evans were doing the training and I was just helping Bob, putting in my two pennyworth’. Unlike Paisley, he was immediately successful. In his first season, Joe Fagan won three trophies.

In 1984, Granada TV made a documentary about football in Liverpool called Home and Away. Its centrepiece was the Milk (League) Cup final between Liverpool and Everton on 25 March, the first time the two clubs had met in a major cup final. Fans of bigger clubs, including Liverpool, now tend to dismiss English football’s third trophy, but the 1984 final was huge. One third of the men in the city, claimed the documentary, left Liverpool to be at the match, including eighteen- year-old Everton fan Keith Cliffe: ‘a gang of us, Red and Blue ... absolutely fantastic’.

Home and Away is a brilliant social history of ‘the giro cup final’. Unemployed men talk about football as the only escape from life on the dole. A Goodison vicar jokes to his sparse congregation about the Christian virtues of an Everton win. Liverpool and Everton fans share a bus south, drinking lager, playing cards, and singing along as someone plays ‘Help’ by the Beatles on his guitar. There are cruel jokes about Jimmy McInnes’s 1965 suicide (‘cut him down, he’s turning blue’) and the Munich disaster, some talk about what ‘the Wembley widows’ are doing back home (Answer: a night out at Flames in Bootle), and some horrific 80s chat up lines in London boozers (‘did you bring your rape insurance policy?’). There’s nostalgia for a lost Liverpool – the 60s folk song ‘In My Liverpool Home’ gets regular airings – and understanding that the city’s reputation is on display. The final was a chance to show Liverpudlians as ‘human beings .. . not a load of scroungers and dogs- bodies’, said Graham Eggerton, an unemployed electrician. If people see supporters together, ‘it can’t all be bad, can it?’

It pays not to get too misty-eyed about the ‘friendly rivalry’ between Liverpool and Everton in the 80s. Chris Wood remembers the November 1982 derby at Goodison not only because of Ian Rush’s four goals in a 5–0 drubbing, but because it was the first time he saw ‘proper fighting’ between Reds and Blues, in the Bullens Road Paddock. Still. It’s hard not to be moved by Wembley Stadium on 25 March 1984. Not by the game, a goalless draw on a rain-soaked pitch. By the fans, who chanted ‘Merseyside, Merseyside’ and ‘Scousers here, Scousers there, Scousers every everywhere’. This was a civic occasion and, The Guardian reported, ‘Merseyside [took] its opportunity for self- advertisement with a flourish’. Stephen Kelly recalled ‘absolutely no hint of violence’. After the final whistle, rival fans hugged and argued over contentious decisions. A group of three Reds and three Blues pushed their broken-down silver Cortina, with red and blue balloons hanging from the aerial, out of the Wembley car park. It was a moment, I think, for those who didn’t want to choose sides, for Liverpudlians like my granddad or Ken, barman at The Vernon on Dale Street, who wore blue socks and a red shirt to serve punters on Cup final weekend. And it was a moment of community solidarity, when the political and economic backdrop – Hatton vs. Thatcher, unemployment – was never far off. Most of the twenty-seven men interviewed in Home and Away were jobless. In 1984, some things were bigger than football. After Everton beat Liverpool at Anfield that October, supporters of both teams sang ‘Arthur Scargill, we’ll support you ever more’ in Yates’s Wine Lodge on Moorfield Street.

Liverpool won the replay at Maine Road 1–0, thanks to Graeme Souness’ twenty-first-minute strike, a left-foot volley after he miscontrolled Phil Neal’s pass. This was Liverpool’s fourth consecutive League Cup and Joe Fagan’s first trophy as manager. Two more were around the corner. After a slow start, Liverpool had the league in hand by late March. Though the lead over Manchester United was just two points, this was Ron Atkinson’s United not Alex Ferguson’s. Liverpool only had to win four of their last ten games to keep United at bay and win a third straight championship. Graeme Souness was blunt: ‘By our own standards, we didn’t deserve to win the title, but by everyone else’s we did’. David Lacey praised the excellence of Souness, Rush, Dalglish, et al., but pondered the ‘scrappy mediocrity’ of the 0–0 draw with Notts County that confirmed the title. What value is a competition, he asked, that prized ‘pace and commitment’ over ‘skill and imagination’? A competition one team dominated in second gear? Liverpool, Lacey concluded, ‘on occasions seemed to be deliberately slowing the pace in order to keep the race alive’.

In 1983/84, Liverpool saved their best for the European Cup. After an easy first-round win over Danish champions Odense, Liverpool drew Spain’s Athletic Bilbao. The 0–0 in the first leg, wrote Stuart Jones in The Times, was like ‘Liverpool lying in the arms of Morpheus. No one could recall a more subdued performance at Anfield’. The second leg was a different story. In a raucous San Mames Stadium, on a pitch that cut up badly, the hosts barely laid a glove on Liverpool, who won thanks to Ian Rush’s sixty-sixth minute header. Fagan called it ‘a magnificent performance’, Souness a better win than Bayern Munich in 1981.

Four days before the Milk Cup final, Liverpool went to the Stadio da Luz in Lisbon and eviscerated Benfica 4–1 to reach the European Cup semi-final. Liverpool’s high-tempo approach after a narrow first-leg victory, so different from the cautious away tactics often deployed by Shankly and Paisley, surprised the hosts. Aided by some bad goalkeeping from Bento, Liverpool cruised into the last four, where Romania’s secret police team, Dinamo Bucharest, awaited. A few fans made their way behind the Iron Curtain for the second leg, as Liverpool again defended a 1–0 lead. Keith Stanton was shocked by the capital’s ‘primitive sights’, proof of the economic catastrophe inflicted by Nicolae Ceauşescu’s dictatorship: ‘horse-drawn carts, women cleaning the roads and plenty of empty shops’. The match was primitive too. Rain poured down on the roofless 23 August Stadium. So did vitriol from 60,000 supporters, most of it aimed at Souness, who’d broken the jaw of Dinamo’s Lică Movilăduring a tetchy first leg. ‘The Romanians kicked mercilessly’, reported Patrick Barclay, but Liverpool were ‘outstanding’ again. Two left-footed finishes from Rush, the first set up by Souness, sent Liverpool to their fourth European Cup final in eight years.

Liverpool now returned to the scene of their greatest triumph, Rome. This time to play the team whose home ground was the Stadio Olimpico, AS Roma. The carnival atmosphere of ’77 was replaced by something edgier. European awareness of the ‘English disease’ had heightened in the intervening years, fed by the press, who loved a hooligan story, by a UK government that saw supporters as a security problem, and by fan misbehaviour. A few weeks before the European Cup final, a young Spurs supporter, Brian Flanagan, was shot dead in a Brussels bar before the UEFA Cup final vs. Anderlecht. More than one hundred Spurs and Anderlecht supporters were arrested, two policemen stabbed, and cars set on fire. Thatcher’s government feared the worst, as did the nervous Italian authorities. ‘There could be trouble at the match in Rome tonight’, read one Whitehall memo from 30 May.

The Minister of Sport, Neil Macfarlane predicted an ‘intense’ atmosphere. Liverpool supporters might face danger, ‘however well behaved themselves’.

In May 1977, Liverpool supporters took over the Stadio Olimpico and Rome. In May 1984, a smaller contingent travelled to the Eternal City, proof of the impact of Thatcherism. Liverpool fans were hemmed in at one end of the ground, surrounded by riot police and their dogs, plus ‘60,000 mad Italians smelling blood’. Marco Catena, a Liverpool fan from Switzerland, at his first European Cup final, remembered the Roma end being full hours before kick-off, ‘flares, noise, songs, drums, smoke, bounce, fuck me they were up for this’.29 Even Bruce Grobbelaar, not the most flappable of men, called the atmosphere ‘frightening’. But Liverpool, who’d won every away game in Europe in 83/84, settled quickly. Souness, in his final game for the club, was dominant, ‘a deliciously phlegmatic performance’ wrote David Lacey. Liverpool took the lead through Phil Neal in the thirteenth minute; Roma equalised just before half-time through Roberto Pruzzo. It was a finely balanced game, absorbing rather than entertaining, and there were no further goals. For the first time, the European Cup final went to penalties. You might know the rest. Stevie Nicol blasting over the bar. Grobbelaar’s spaghetti legs. Misses from Conti and Graziani. Alan Kennedy, a ‘shocking’ penalty taker at Melwood, sending Franco Tancredi the wrong way. Liverpool’s fourth European Cup. ‘Thoroughly deserved’, reckoned The Guardian. Souness, the man of the hour, called it ‘possibly the greatest result ever achieved by a club side’.

National headlines on 31 May focused on violence at home: another pitched battle between police and striking miners at the Orgreave coking pit in South Yorkshire. A burned Portakabin, riot gear, police dogs, mounted police injuries, and arrests, including that of NUM President Arthur Scargill. Echoes of Brixton and Toxteth in 1981. Desperate protestors, stigmatised as ‘rioters’, taking a stand against an unsympathetic state and its repressive, mendacious enforcers. We’ll be hearing again, of course, from South Yorkshire Police.

Tucked on the inside pages, a tale of violence abroad didn’t get the same coverage. Perhaps because it was committed against, rather than by, English supporters, which didn’t fit the hooligan narratives of the day. There were nasty scenes in Rome after Liverpool’s victory. David Pye, a graduate student at the University of Brighton, recalled being ambushed by Roma ultras armed with ‘baseball bats, clubs, chair legs, pool cues, chains and knives’.31 Bricks were thrown at Liverpool coaches from moving Fiats, supporters on foot were slashed in the buttocks by masked men on Vespas. Stephen Monaghan remembered ‘everyone was getting attacked, women, children, the elderly’. The police were little help. As many as ninety Liverpool fans required hospital treatment, many for knife wounds. George Sharp, forty- seven, from Halewood, was stabbed in the kidneys. He needed four hours of emergency surgery to save his life.

The British Embassy reported that Liverpool supporters ‘behaved just as we expected – in an exemplary manner’. Walking away from the stadium after the game, Marco Catena and his mates (two Scousers, an Austrian, and a German) helped an Italian push his broken-down Fiat 500 off the road. Stuck in the one-horse town of Ladispoli for a week before the final, Stephen Monaghan and his mates befriended the local policeman, Angelo, and some of the hooligans who’d initially wanted to fight their Scouse visitors. He ended up having dinner at the hooligan leader’s house. Mono brought flowers for the guy’s Mum and tasted his first spaghetti bolognaise. Liverpool fans and locals then played a ‘peace match’: ‘[they] loved us in the end’. Sadly, it was memories of the violence – frightening, humiliating, and under- reported – not the friendships and celebrations that predominated when Liverpool travelled to Belgium to meet another Italian club, Juventus, in the 1985 European Cup final. ‘In the minds of the worst affected’, wrote Brian Reade, ‘someone had to pay’.

***

In the summer of 1987, after spells at five clubs, Howard Gayle joined Blackburn Rovers. Rovers hadn’t had a Black player in its ninety-nine- year history. Hardly an ideal move, but Gayle didn’t have many options. He spent five years at the club, scoring twenty-nine goals in 116 games. The flame was still bright. One fan remembers Gayle clambering into the Nuttall Street Paddock to challenge someone who said something as he warmed up. As Tommy Smith could testify, Gayle confronted racism whenever and wherever he found it. Which, in English football in the 70s and 80s, meant often and everywhere.

The same summer, Liverpool FC signed their second Black player. Watford winger John Barnes was a different character to Gayle – and a better player. There’s a picture of Barnes and fellow new signing Peter Beardsley outside Anfield. On the ‘No ball games allowed’ sign above them, you can see ‘NF’, the insignia of the far-right National Front. I first saw that photo in Dave Hill’s Out of His Skin, which has other shots of racist graffiti on the Kop’s brick walls in the mid-80s. ‘White power’. ‘There’s no black in the Union Jack’. ‘Liverpool are white’. John Barnes saw all this. He got letters. ‘You are crap, go back to Africa and swing from the trees’. The club got many more.

Peter Furmedge felt attitudes changed on the Kop before John Barnes arrived. A younger, more politicised generation – that read The End, supported Rock against Racism, and loved the Specials – ‘kicked back against the racism’. Barnes, in Furmedge’s view, ‘tipped the bal- ance’. His brilliance brought the silent majority into the anti-racist camp. Performance was key, as Barnes understood. ‘The Kop would have slaughtered me with racial abuse if I had faltered on the field’. It also helped that Barnes, the son of a Jamaican colonel, was less confrontational than Gayle. He was seen as a more acceptable Black footballer, someone who could take, and make, a joke. Racists bemused rather than angered Barnes. He came to his first players’ Christmas party dressed as a Ku Klux Klansman. Bob Thomas’ photo from the Merseyside derby at Goodison in February 1988 shows Barnes back- heeling off the pitch one of the bananas thrown at him that day. For Emy Onuora, a Black Everton supporter, it was an awkward time: ‘I knew the abuse he was going to get was just going to be something that .. . I was just going to remove myself from’.

A comforting story can take you from Liverpool ’81 to Liverpool ’88. It emphasises transformation, in the city’s attitudes to race and in its economic fortunes. From the ostracised Howard Gayle to the feted John Barnes.

By 1988, The End was nearing the end. The twentieth and final issue came out shortly after the February game vs. Everton, an FA Cup tie watched by millions on BBC Television. In one of its best pieces, the magazine condemned not only the Goodison racists who chanted ‘N*****pool’, but the Liverpool fans who’d brought bananas to Arsenal for Barnes’ LFC debut. The silence of local media about ‘prob- ably the worst incidents of racial bigotry ever seen at a football ground’. The reluctance of players, managers, and chairmen to publicly condemn racism, often downplayed as the work of a ‘lunatic fringe’. All the structures and institutions that enabled racism on Merseyside, a place where, as the Community Relations Council despaired in 1986, ‘there was an almost total exclusion of black people from most job opportun- ities’. Where, claimed local magazine Black Linx in the same year, there was ‘a more subtle form of apartheid than Johannesburg’.35

A comforting story can take you from Liverpool ’81 to Liverpool ’88. It emphasises transformation, in the city’s attitudes to race and in the city’s economic fortunes. From the ostracised Howard Gayle to the feted John Barnes, from Anfield monkey chants to ‘The Anfield Rap’ (‘I come from Jamaica/My name is John Barn-es/When I do my thing/The crowd go bananas’), from the Toxteth riots to the reopen- ing of the Albert Dock as a tourist attraction, home to the Tate Liverpool and The Beatles Story.

Liverpool returned to Goodison a month after the poisonous match in February 1988. Already, Barnes recalled, things were better. No bananas, little overt racism. Rogan Taylor, meanwhile, saw the Kop re-educated before his eyes. Evertonian racism towards Liverpool’s best player made Kopites protective of Barnes and more aware of the absurd- ity of booing other teams’ Black players. As Rainer Werner Fassbinder shows in Fear Eats the Soul, his great film about racism in 70s West

Germany, prejudice is often overcome through self-interest not ideal- ism. So it was with John Barnes at LFC. The ‘sudden saintliness’ of Main Stand season ticket holders, who’d once screamed at ‘black bastards’ and now embraced one, struck Stephen Kelly as funny. But it was a transformation nonetheless, one that diversified Liverpool’s fan base. Emy Onuora’s brother was living in London. ‘A lot of his Black friends were Liverpool fans because of John Barnes’.

John Barnes doubted how much had changed. ‘It’s easy to love John Barnes, but people must love the black guy without the fame, money or special skill’.36 Some Liverpool fans, he noticed, still booed opposition Black players, like Norwich’s Ruel Fox. The Gifford Report (1989) would have confirmed Barnes’, and The End’s, scepticism. It called race relations in Liverpool ‘uniquely horrific’. Black people faced disproportionately high rates of unemployment and ‘a devastating lack of mobility’. Like many L8 residents, Gifford felt not enough had changed since 1981. Regeneration projects like the Albert Dock didn’t benefit the city’s Black communities. Like the figure of John Barnes, the new or reclaimed buildings gave an impression of change not matched by reality.

Though L8 was on Anfield’s doorstep, there seemed to be an unspoken consensus that young players from the area ‘don’t get any- where near Liverpool’.37 Nor did many Black supporters. Steve Skeete, who once had a trial at Melwood alongside Howard Gayle, remembered going to Anfield, red scarf around his neck, and being chased out of the ground all the way to Hall Lane in Kensington by a hundred fellow supporters yelling ‘get the n*****’. Liverpool FC, like most Division One clubs at the end of the 80s, remained a predominantly white club with a predominantly white fan base. Peter Robinson felt it was ‘strange’ LFC had never had ‘a large Black following’: ‘And that hasn’t increased much with the coming of John Barnes’.38 But it wasn’t strange, given the experiences of Skeete, Onuora at Everton, or Spurs fan Paul Duhaney, too ‘shit scared’ to go to away games until the 90s. Even in the Premier League era, when the English game diversified, it was still often the case that ‘Black people play, they don’t go’.39

Liverpool FC didn’t seek change in the Boot Room era. The club’s run of success was based, to an almost superstitious degree, on repetition in training and matchday routines and the timely turnover of players and staff, all of whom became versed in ‘the Liverpool way’. But change has a way of finding you anyway. On the surface, LFC in the

80s – John Smith’s humblebrag ‘modest club’– was a shining example of the virtues of continuity. Three managers, all promoted from within. Six leagues, two European Cups, four League Cups, two FA Cups. But two events drove fault lines through this success story, changing the direction of LFC and English football. We need to talk about Heysel. And we need to talk about Hillsborough. Because, on and off the field after 1989, Liverpool FC would be – for the longest time, and for the first time in a long time – on the wrong side of history.

About the Book: Dreams and Songs to Sing is a global, people’s history of Liverpool FC, told through the voices of its supporters. Blending interviews, letters, and eyewitness accounts, Alan McDougall captures the club’s emotional, cultural, and social journey from Shankly to Klopp.

About the Author: Alan McDougall is a historian and lifelong Liverpool supporter whose work explores the intersections of sport, culture, and society. A professor of history at the University of Guelph in Canada, he has written widely on football, politics, and popular culture. Dreams and Songs to Sing combines his academic insight with a fan’s passion, offering a deeply human portrait of the game and the people who make it matter.

This was fantastic thank you. I have read 'Two Tribes' and 'I don't know what it is but i love it' by Tony Evans. Now I need to read this. Such an interesting time in Liverpool history, the city and the club. Horrible what Howard Gayle went through. It was good to see the video recently of him at Liverpool training and him and Curtis Jones walking around Liverpool 8.